Beneath the Surface: The Hidden Cost of Competition in the South China Sea

Submitted to the Harvard International Review.

With experts warning of a Fourth Taiwan Strait Crisis following US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s high-profile Taiwan visit, tensions in the Indo-Pacific have once again been thrown into sharp relief. Yet, as the world turns its attention to the far-reaching implications of hostilities in the South China Sea, a very different kind of catastrophe is looming below its troubled waters.

The South China Sea’s (SCS’s) significance to international prosperity and security cannot be overstated. An estimated one-third of global shipping transits the region, amounting to more than US$3.4 trillion of maritime trade annually. Its lucrative fisheries are vital to food security in Asia, producing some 12% of the world’s seafood catch, and vast deposits of oil and natural gas are said to lie beneath its seabed, promising untold energy riches for countries able to assert control.

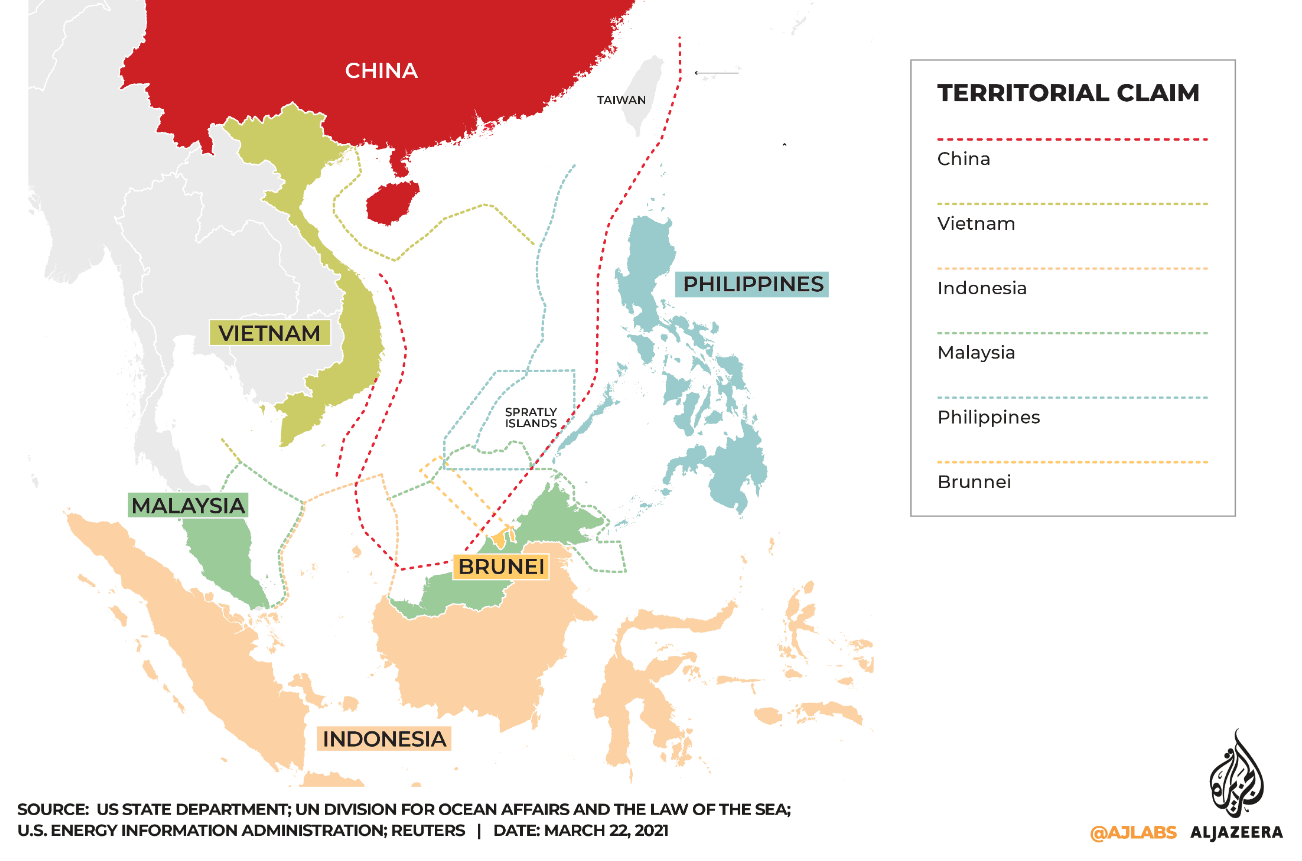

This economic value, coupled with the SCS’s strategic location as a potential base of military operations in a future conflict in the Pacific, has led both littoral states and major powers to vie for dominance over the waters. As it stands, 6 sovereign nations (and Taiwan) lay competing claims over various islets and waterways in the sea.

Unfortunately, while much of the focus on the region continues to center around these territorial disputes and the growing geopolitical rivalry between China and the United States, another crucial dimension of the conflict has often been overlooked. The SCS is home to one of the most diverse marine ecosystems in the world, containing thousands of mangrove, fish and sponge species, with 571 known varieties of coral reef alone. Yet, decades of land grabs and unsustainable fishing practices have caused the destruction of this environmental gem – with dire consequences for the region and the world at large.

Background of the Disputes

The SCS contains two main island chains, the Paracels in the northwest and the Spratlys in the southeast. Although the statuses of the islands were left undetermined after World War 2, competition for control only began in earnest after a 1969 UN report found “substantial energy deposits” in the seabed. Following a violent skirmish in 1974, China ousted South Vietnamese troops from the Paracels, establishing de facto control over the archipelago. The ensuing decades saw other countries enter the mix, with the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia declaring sovereignty over parts of the islands and their surrounding waters.

China’s claims are largely delineated by a so-called “nine-dash line” – a 7-decade-old declaration inherited from the nationalist Kuomintang government that ruled China before 1949. The symbolic boundary, which covers 90% of the SCS, has alarmed China’s Southeast Asian neighbors because it overlaps with many of their Exclusive Economic Zones – where they enjoy special rights to the exploration and use of marine resources. China’s ambitions have also drawn the attention of other major powers such as the United States, which routinely conducts “freedom of navigation” exercises to counter China’s increasingly assertive posture.

Intensification and Environmental Impact

In recent years, tensions have set off a scramble for control through aggressive land reclamation. China, alone, has built an estimated 3,200 acres of artificial islands in the Spratlys, some of which include military bases with advanced missile systems and aircraft installations. Rivals like Vietnam and the Philippines have followed suit, building 49 and 9 outposts respectively.

These activities have taken a heavy toll on native marine life. The dredging process used to build islands involves breaking up reefs and pouring sand onto living coral, killing them by blocking their access to sunlight. Coral reefs “support more species per unit area than any other marine environment”, and provide natural protection for larvae, which are essential to the life cycle of fish. Their destruction represents not only poor stewardship of the SCS’s rich natural environment, but also threatens the food security of millions who depend on its seafood as a vital source of protein.

Apart from engaging in an island-building frenzy, parties to the disputes have also attempted to legitimize their territorial claims by expanding their fishing operations. China has gone as far as to pay fishermen to maintain a presence in the Spratly islands, while Vietnam has deployed a “maritime militia” of armed fishing boats to protect its interests. Other states like Indonesia and the Philippines have also bolstered their fleets to increase hauls. This overfishing has caused catch rates in the SCS to decline by an estimated 70 to 95% since the 1950s, exacerbating the already dire situation.

The environmental degradation caused by this heated geopolitical contest compounds existing problems such as land and ship-based pollution, coral bleaching, and rising sea levels. Based on the current trajectory, fish stocks in the SCS are slated to drop a further 63% by 2100, resulting in the near or total collapse of surrounding fisheries. Yet, even as projections show that Southeast Asia will bear the brunt of this environmental crisis, littoral states continue to engage in nationalistic brinkmanship while disregarding the natural heritage of the SCS and the devastating consequences that its destruction will have on their populations.

Potential Avenues of Cooperation

Past efforts at cooperation in the SCS have largely revolved around preventing armed conflict. Agreements such as the 1992 ASEAN Declaration on the South China Sea and the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea have, however, borne little fruit because of their non-binding nature. Evidencing this, violent clashes have broken out as recently as in November 2021, when Chinese coast guard vessels fired water cannons at Philippine naval supply boats.

While the prospect of reaching a political settlement in the SCS appears increasingly elusive, the looming environmental crisis presents a golden opportunity for states to set aside their differences in favor of scientific and economic collaboration. Common interests in combating rising sea levels and depleting fish stocks could be a starting point for joint marine conservation and resource management. To achieve this, policymakers could look to existing models such as the Arctic Council, which has adopted several legally binding agreements upholding environmental protection and sustainability. Other precedents like the Joint Norwegian–Russian Fisheries Commission, which has managed fishing in the Barents Sea since the height of the Cold War, could also provide a blueprint for cooperation in the SCS.

To conclude, an ecological catastrophe in the SCS will have disastrous ripple effects for the region and beyond. While littoral states will be hit especially hard, the sea is also a vital carbon sink for the rest of the world, and a sanctuary for marine life which cannot be found anywhere else on earth. The devastation of this environmental gem is a truly global issue, and the time has come for nations to cease pursuing narrow interests at the expense of our collective future.